The greatest treasure I have found after five decades in archeology Countercurrents

With my newly graduated university degree, I sat down for breakfast with my entrepreneurial grandfather, who hit me with the question: “So you want to study archaeology, go to graduate school, how are you going to make a living, digging for treasure?” My outraged Answer was “No” because that was never the plan and was clearly contrary to my training and ethics. And yet, despite the family doubts: “Why not do business?” I decided to follow the path I had chosen; a life in which he taught, researched and wrote about times gone by and the many lives that occupied them.

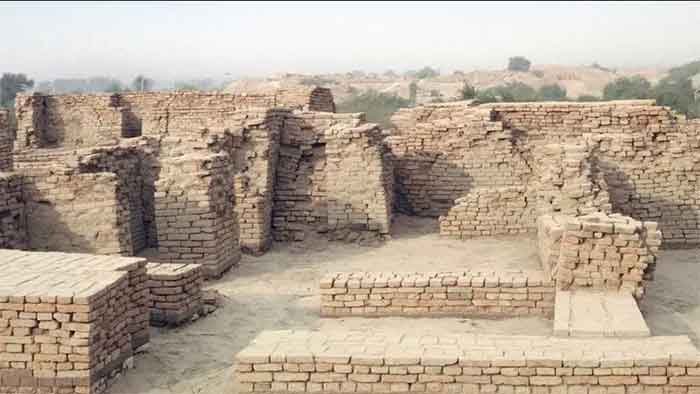

An analytical lens across the depths of time is archaeology’s greatest attribute. Since the mid-20th century, tens of thousands of archaeologists and their collaborators have examined the material remains of human activity dating back to the earliest arrival of our ancestors on six continents. Our record of human careers is much more temporally, spatially extensive, and diverse than what was imagined 50 to 75 years ago. Beyond its temporal depth and global reach, archeology, unlike written texts, is not fundamentally focused on “the winners,” that is, those with political power and/or economic influence. Archeology data derived from the earth can neither pretend nor exaggerate.

As an archaeologist, my view of humanity’s past has been enriched and expanded by the privilege of conducting decades of fieldwork in centers of civilization – Mesoamerica and China; 25 years working in a large museum; the co-author of nine editions of a general textbook on global archaeology; and more than 30 years of experience editing articles on synthetic archeology for a major journal. I learned how meaningful the past can be to people and how the examination of humanity’s career must be done with integrity. As archeology and history researchers around the world gather information, we recognize that the paths of human history have not been uniform. Our past was not static either. The interpersonal affiliations, institutions, and agglomerations that we have formed over millennia, including cities and states, have not expanded linearly over time toward a single unified goal or outcome. They did not move gradually or at the same pace through a ladder of successive steps. Gone is the time when it seemed legitimate to assume that most of what was relevant in history happened in or could be gleaned exclusively from the middle latitudes of Eurasia. The grand narratives that offered universal explanations based on race, geography, environment, inherent human nature, and even demographic growth can no longer be sustained in the face of evidence.

Recognizing alternative paths in humanity’s past is no reason to ignore, selectively straitjacket, or gloss over our collective histories. Just as it is now inappropriate to assume that the classical Mediterranean world or medieval Europe are appropriate proxies for a homogeneous human past, so too is it short-sighted to claim that the pasts of non-Western peoples were unchanging or utopian.

In the past or in the present, people are people, always selfish and yet the best collaborators with non-relatives on the planet. And our cooperation agreements do not always have to be made from the top down. Rather, we work together by creating rules and institutions that establish norms of practice that are contingent and situational, but can also be permanent.

We must now grapple with the empirical reality that our collective past was more heterogeneous and complex than previously thought. This is not a moment of despair, but a crucial opportunity. We now have a rare opportunity to systematically and concertedly compare and contrast the different ways in which people have met the challenges of the past. Archeology and history give us the information and tools to examine and explain how people dealt with problems in the past. These studies enable us to recognize and evaluate patterns that would otherwise remain hidden in the present – and provide a critical advantage in deciphering and understanding alternative outcomes.

The comparative global perspective of archeology provides an empirical basis for seeing what worked and what did not, and what was sustainable and what was not. Serious, holistic and empirically based perspectives on humanity’s past provide a balance sheet that, when carefully accumulated and scientifically examined, provides insights to avoid the daydreams and dark visions too often associated with the past, as well as the potential ones Nightmares on the threshold of our future. We have learned that neither our genes, our ancestry nor our geographical environmental conditions fully determine the path that lies ahead of us. To a certain extent, we as people and the institutions we belong to help shape what is to come; The compendium of knowledge gained through archeology and history provides us with a rich archive of alternative roadmaps, practices and consequences that are crucial to defining and determining the choices we must make together in the future.

After five decades in archaeology, I have come to realize that, in a way, my grandfather was right. I have found a treasure – information, perspectives and insights relevant to unraveling humanity’s past and its significance for the present and their shared future.

Gary M. Feinman is MacArthur Curator of Anthropology at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois.

This article was created by Human bridges.